Parasites can play important roles in keeping ecosystems intact. But conservation efforts have largely ignored them because of their association with human disease. Meanwhile, many species are disappearing before they have even been documented. A new international parasite biobank aims to systematically collect and store parasite samples from around the world to make them available to scientists internationally for research.

Of the 100,000 to 350,000 species of helminth endoparasites that infect vertebrates globally, 85-95% are poorly documented.

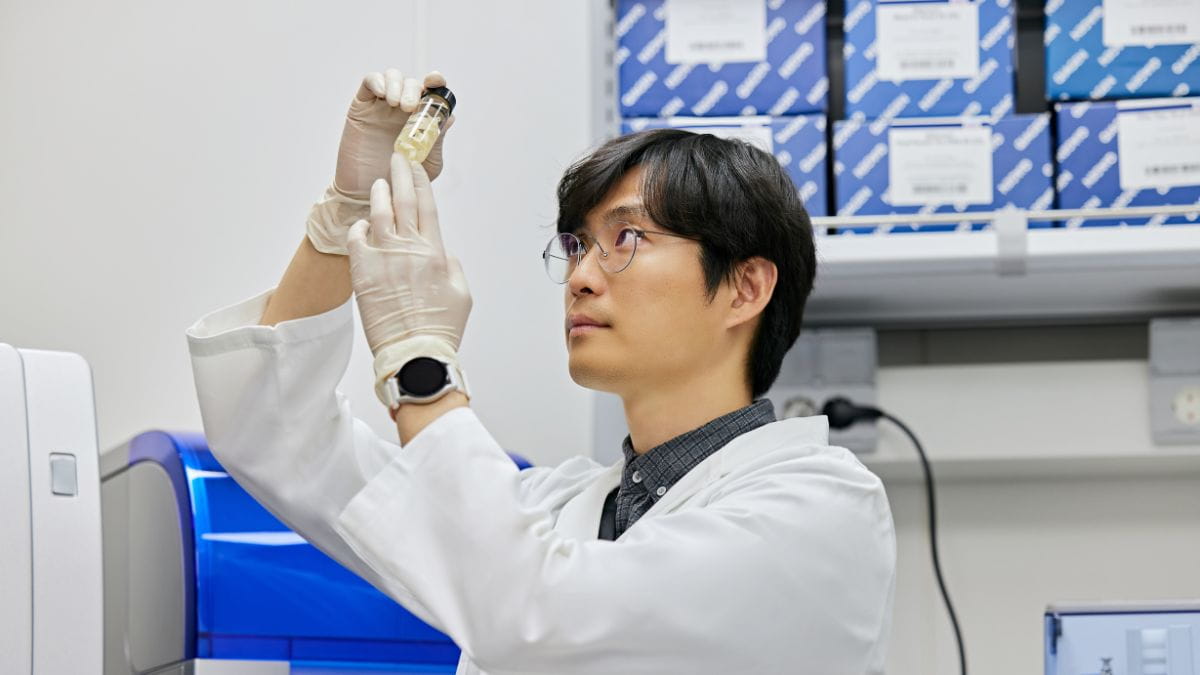

Dongmin Lee, PhD, Chief Operating Officer, International Parasite Resource Biobank

Species that do not infect humans play critical roles in our ecosystems, including ways that directly benefit us.

Skylar Hopkins, PhD, assistant professor, Department of applied ecology at North Carolina State University

We provide researchers the products, services and resources they require to carry out significant life science research.

Dongmin Lee, PhD, Chief Operating Officer, International Parasite Resource Biobank

iPRB has chosen QIAGEN’s workflow solutions for molecular analyses because automation reduces the potential for human error.

Dongmin Lee, PhD, Chief Operating Officer, International Parasite Resource Biobank

August 2023