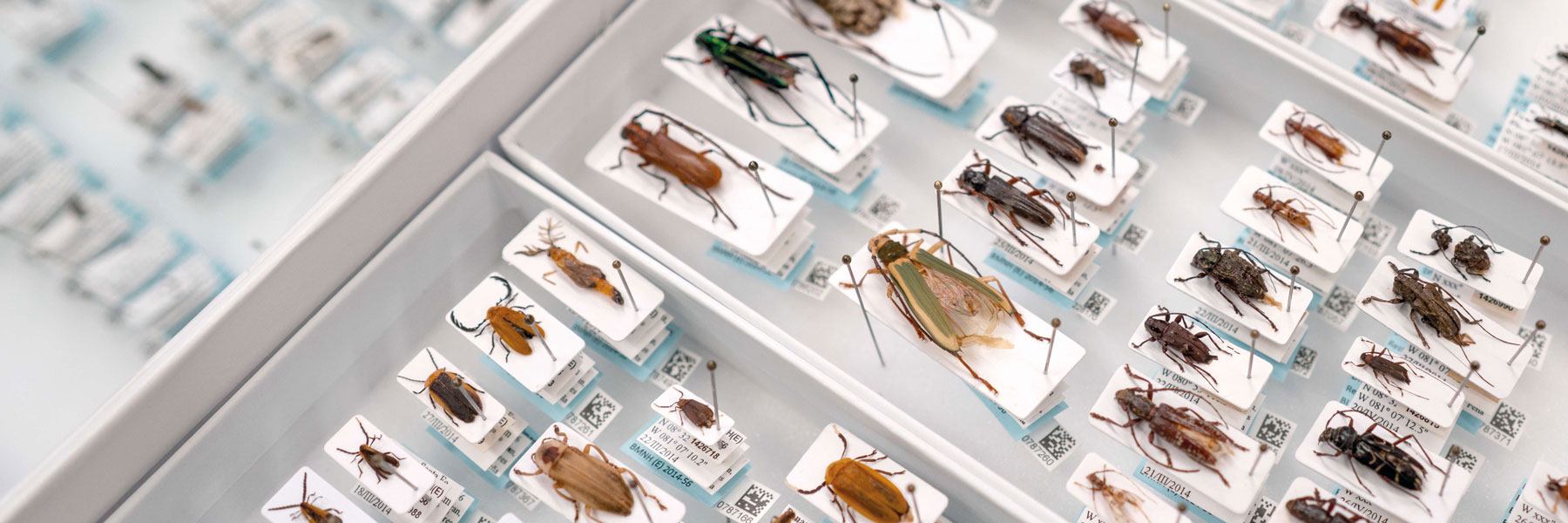

How do you identify an ancient piece of bone, a single piece of fur or a crushed insect leg? Millions of varied and often contaminated samples have passed through the hands of sequencing expert, Claire Griffin, over the years, and she continues to find new ways to identify the stranger side of nature hidden in every type of tissue sample imaginable.

We receive a lot of different types of tissues and materials – teeth, bone, furs, insects - and it’s our job to provide sequencing data for those samples.

Claire Griffin, Senior Sequencing Technician, Natural History Museum, London

We receive samples often contaminated with rodent DNA, bacteria or fungus. They pose some challenges in getting the correct sequence rather than the contamination.

Claire Griffin, Senior Sequencing Technician, Natural History Museum, London

The DNeasy blood and tissue kit is the one I opt for most often for a wide range of sample types, because it gives us high-quality DNA, even with tricky samples.

Claire Griffin, Senior Sequencing Technician, Natural History Museum, London

May 2021